I used to avoid discussing my students’ reading difficulties with their families. I didn’t realize I was withholding information, but in retrospect I see that, in parent/teacher conferences and on report cards, I’d focus on a child’s strengths even if multiple data points showed they were below benchmark. I would share how I was teaching and give suggestions for helping at home–but I never said, “Your child is behind in

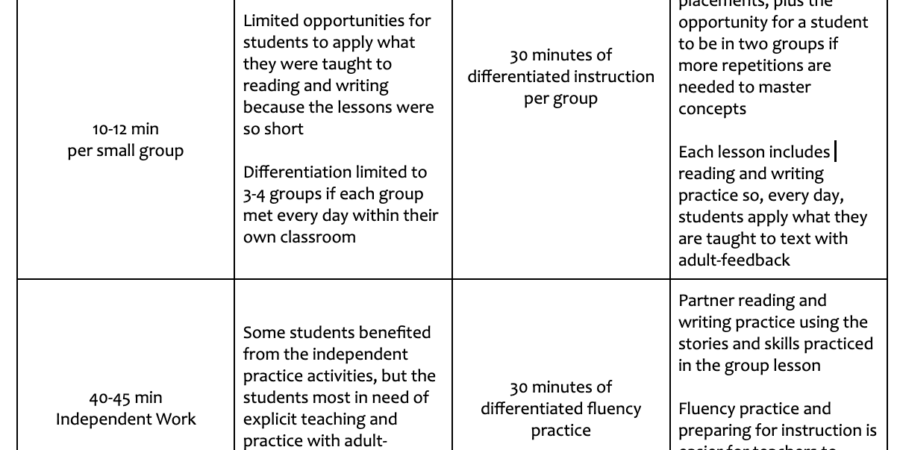

Differentiation Done Right: How “Walk To Read” Works

When we’re asked to switch to explicit, systematic instruction, many teachers worry that we’ll no longer be able to tailor our teaching to the students in front of us. Calls for whole-class phonics instruction lasting 30-45 minutes, for example, summon fears that our students will be bored by concepts they already know or aren’t yet ready for. And they resurface memories of teachers stripped of our ability to differentiate instruction as

Data: The closest thing we have to a crystal ball

I embraced every possible reason not to take early literacy data seriously: Kindergarteners are too young for testing. How can we trust reading data of kids who have barely been in school? Shouldn’t we wait and see if students will catch up? I don’t even care about these subtests. Screening measures don’t tell me what I really need to know in order to teach. Testing pulls time away from instruction.

F&P Benchmark Assessment System: Doesn’t look right, sound right, or make sense

My district, like so many others, uses Fountas and Pinnell’s Benchmark Assessment System (BAS) as the primary measure of student reading progress. But if you’ve had doubts about the assessment and the ways BAS data is often used, you’re on to something… Limited Materials An F&P Benchmark Assessment System kit provides us with only two books (one fiction and one nonfiction) for each reading level, so we end up using