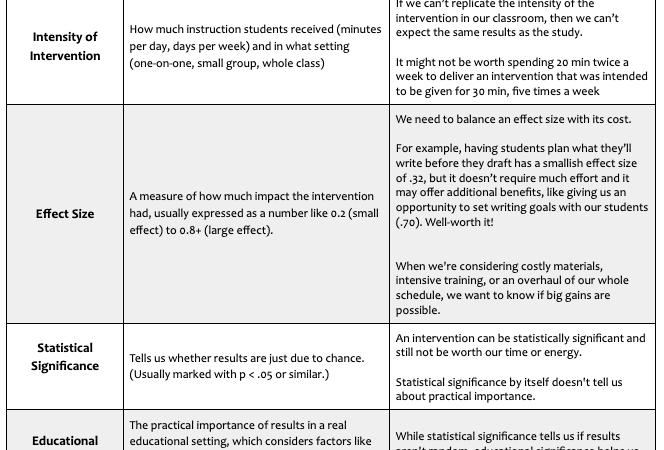

Minding the Research to Practice Gap Following the reading research is more challenging than it sounds. There are thousands of studies and it’s hard to know where to start. For classroom teachers, making sense of studies is extra challenging because a lot (but not all!) of the research has been done in contexts that we can’t replicate– intensive doses of reading intervention, delivered one-on-one, in environments with fewer competing priorities.

Classroom Observations: We Should Do Them, So Why Don’t We?

As a classroom teacher, I felt anxious when visitors observed, so as a coach I attributed my nervousness about observations to sympathy pains. But now I know that principals, vice principals, and even coaches rarely watch instruction, and I’ve heard many confessions like this: “I realized that the biggest barrier was in my own head. I actually felt shy about going into classrooms for an in-depth look. It was as

The Standards Trap: Why Grade-Level Teaching Fails Our Students

The Common Core Standards were marketed as a great equalizer—if we provided standards-aligned lessons, then all students would be prepared for college and career. But the more I learn about effective reading instruction, the more I realize that the obsession with standards alignment may be pulling us away from the teaching our students actually need. Near-Perfect Reviews, Imperfect Results I felt something was off in the comprehension lesson plans in

Does it Really Matter How Kids Are Taught, If They Eventually Learn How to Read?

I loved my first grade teacher, but she didn’t teach me how to read. The Start of a Problem Mrs. B earned her teaching credential during the height of Whole-Language. She read aloud to us every day and led projects related to books– making moon hats like Little Bear and our own Stone Soup. For a whole-class rendition of Where the Wild Things Are, a parent volunteer taped construction paper

Doubt Crept In: Questioning My Faith in Reading Research

Uh oh I thought that the more I knew about the science of reading, the better my teaching would become. And I’ve staked so much of my identity on this belief that my newfound doubt has shaken me terribly. At a recent conference for reading researchers, I realized: “There is a whole world of reading science that is not meant for me.” Panicked, I said to a researcher-friend: “Please tell

Hoping for the Best is Not a Viable Strategy

We’re keeping our worries about the Science of Reading movement quiet, afraid that voicing them will somehow increase the chances that it could fail. But anyone who cares deeply about its success is plagued by “what ifs” that keep us up at night. What if we fall short because… Anyone knowledgeable about reading research and what’s happening in classrooms has worries like these. But most of us have remained quiet,

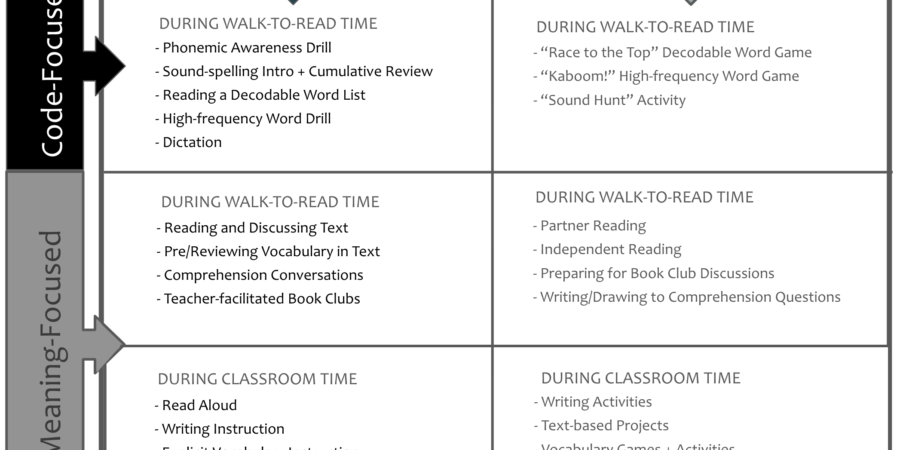

What does your literacy block look like? It depends…

Schools all over the country are changing how reading is taught and they face two big questions: Decisions about what will be taught, when, and for how many minutes will determine the daily experience of students, and how much they’ll learn in school. Instructional time is limited, so building classroom schedules requires a series of choices that ultimately reflect our values. Looking back at my old schedules, I can see

Grasping for Meaning: What it’s Like to Struggle with Reading Comprehension

I thought experiencing reading difficulty of our own could help us relate to the comprehension challenges that our students face, so I planned a professional development session for the teachers at my school. To select a text to share, I followed the parameters we often use when choosing passages for students: But also, it was really hard. I prepared a lesson by drafting questions, collecting kid-friendly/teacher-friendly definitions for the challenging

When Language Is a Wall

When I began to learn about phonics instruction, I saw spelling puzzles in words I’d never noticed before, and I gained appreciation for the difficulty of learning to decode. Now, as an increasing number of students at my school can read accurately, the challenge of comprehension is looming large. It’s hard to identify potential barriers to comprehension when students read a text we ourselves can easily understand. And it’s harder

New (School) Year’s Resolutions

Perfect Isn’t Possible I love the bustle of a new school year. In the days before school starts, I organize and label absolutely everything, from the books in my classroom library to the blocks of time in my planbook. I remember and laugh at my grandma’s joke– “Everything’s perfect until the kids come!”– but still I spend hours color coding and alphabetizing. Kids will doodle on their notebooks, glue sticks