I used to avoid discussing my students’ reading difficulties with their families. I didn’t realize I was withholding information, but in retrospect I see that, in parent/teacher conferences and on report cards, I’d focus on a child’s strengths even if multiple data points showed they were below benchmark.

I would share how I was teaching and give suggestions for helping at home–but I never said, “Your child is behind in reading and there is cause for concern.”

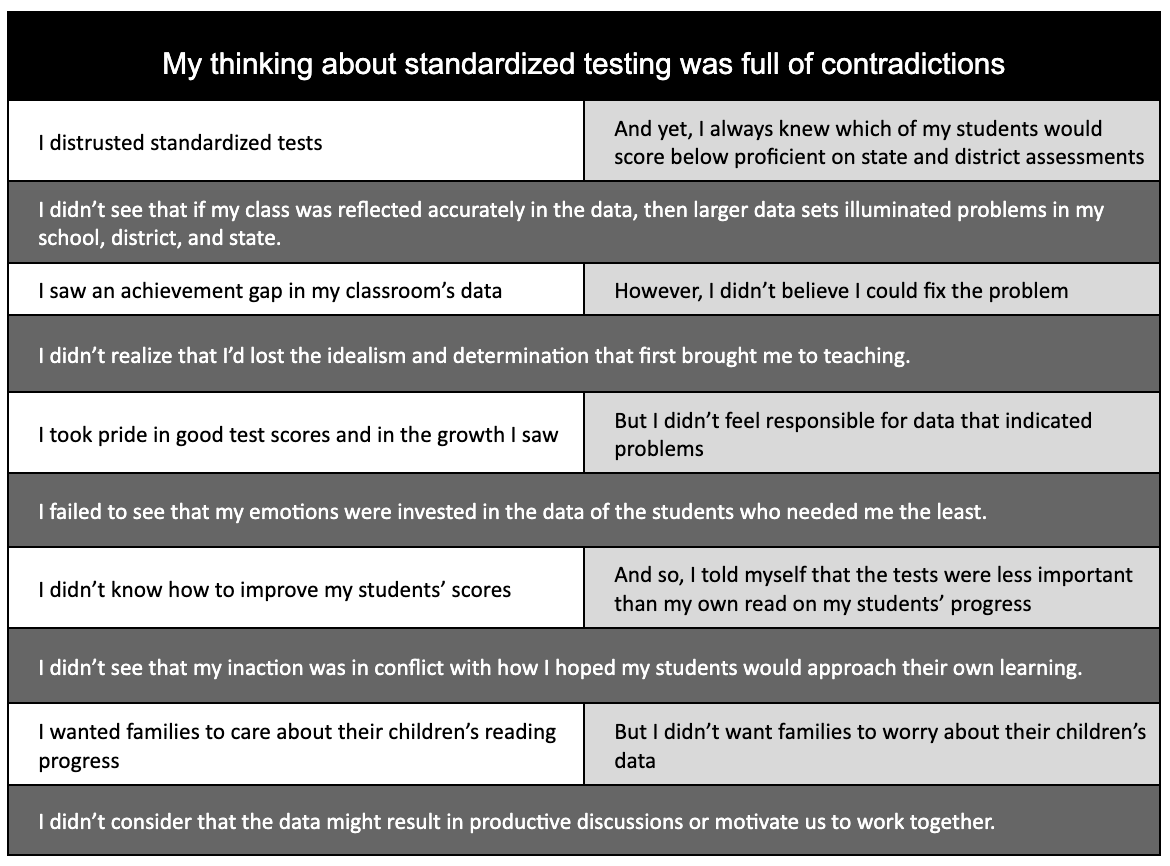

If someone had asked me why I didn’t look at standardized test scores with my students’ families, I might have said, “The data’s not very helpful” or “I don’t believe it’s relevant.”

A recent survey shows that I wasn’t unique. When asked to rank the most important ways to understand a child’s achievement, teachers rated standardized tests below: in-class observations, results from teacher-created assessments, and interactions with students.

Now that I understand objective measures of reading, my appreciation of them has grown. But for a long time, my thoughts and feelings about test scores were a tangled mess.

In upcoming blogs, I’ll explain how my understanding of testing has changed, how I now use data, and what information I share with families.

But at this moment, I want to explore just one idea:

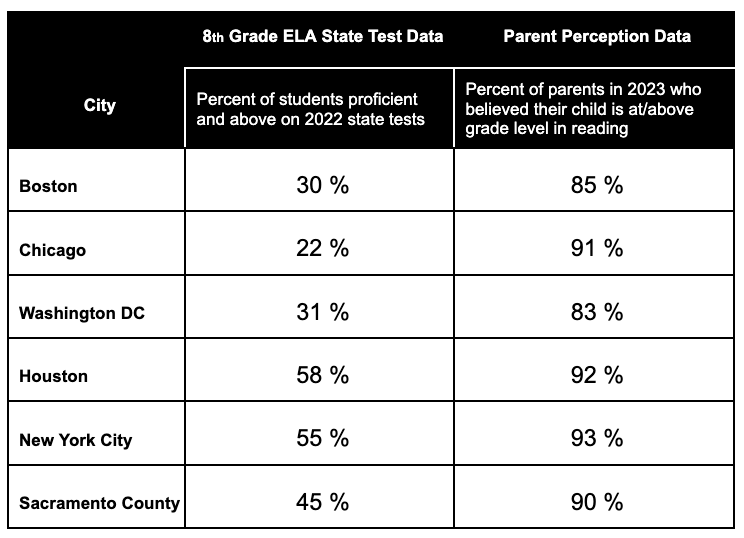

No matter my feelings about standardized testing, I could still predict my students’ scores. Which is why this recent ad campaign and the survey data it reflects is so important.

According to surveys, parents overestimated their children’s reading abilities.

A quote in a news article on the topic sums things up:

“Parents can’t solve a problem that they don’t know they have.”

And former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan recently spoke about the gap between how families perceive their children’s performance and their actual scores:

“It’s not just a perception gap. It’s a reality gap. And it actually breaks my heart… the fact that we’re being dishonest, both with students but also with their parents, we’re missing a massive opportunity to help parents help their children to catch up.”

He’s right. And whether or not educators feel conflicted about standardized testing, we know how well our students will do on those tests, and that means that we have a duty to explain the data to our students’ families.

If we’re worried that parents will be surprised, frustrated, or even angry, we can prepare ourselves with some possible responses. But we have to give families a chance to understand their children’s current abilities while they have an opportunity to take action.

“Many districts have poured their federal pandemic recovery money into summer school offerings, tutoring programs and other interventions to help students regain ground lost during the pandemic. But the uptake hasn’t been what educators hoped. If more parents knew their children were behind academically, they might seek help.”

Many kids are struggling in school. Do their parents know?

Low scores on standardized tests are a red flag, and if teachers are the only ones seeing those flags waving, kids miss out on support from the people who will care for them long after this school year is over.