As a classroom teacher, I felt anxious when visitors observed, so as a coach I attributed my nervousness about observations to sympathy pains. But now I know that principals, vice principals, and even coaches rarely watch instruction, and I’ve heard many confessions like this: “I realized that the biggest barrier was in my own head. I actually felt shy about going into classrooms for an in-depth look. It was as

Getting Reading Right Is Messy: No One Has It All Figured Out

“I wish my school were like that.” I clicked through a slidedeck about a literacy improvement plan and I felt a pang of envy. “I wish my work was so straightforward and my school’s progress so steady.” But these were my slides. The students, teachers, moments captured in photographs, and ideas represented in bullet points–they were all from my school. So why, while looking at evidence of my school’s improvement,

Hoping for the Best is Not a Viable Strategy

We’re keeping our worries about the Science of Reading movement quiet, afraid that voicing them will somehow increase the chances that it could fail. But anyone who cares deeply about its success is plagued by “what ifs” that keep us up at night. What if we fall short because… Anyone knowledgeable about reading research and what’s happening in classrooms has worries like these. But most of us have remained quiet,

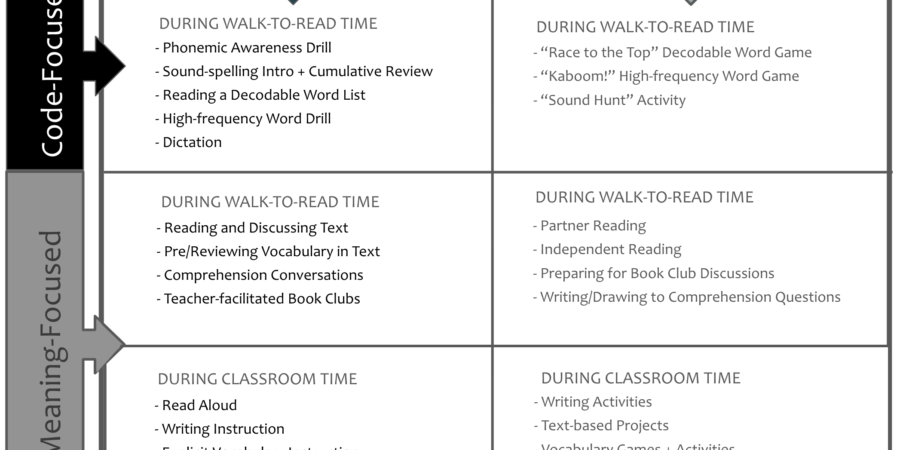

What does your literacy block look like? It depends…

Schools all over the country are changing how reading is taught and they face two big questions: Decisions about what will be taught, when, and for how many minutes will determine the daily experience of students, and how much they’ll learn in school. Instructional time is limited, so building classroom schedules requires a series of choices that ultimately reflect our values. Looking back at my old schedules, I can see

It’s Not Enough to Mean Well

I came into the teaching profession aware that my White middle class experience would impact how I taught. I earned my teaching credential and masters degree from a program focused on social justice. There, I’d read and discussed books such as Teaching Other People’s Children and Bad Boys: Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity, so I understood, in theory, the blindness and biases I would need to overcome.

Making Changes that Last: The End of the Pendulum?

There’s new momentum behind teaching reading more directly and explicitly, but many of us are wondering: is this just another swing of a pendulum? It’s hard to believe that investing in new reading practices is worthwhile if the new practices will fall out of favor in a few years. But for district leaders who want to make a lasting impact, there is no better focus than reading instruction– and, if

Shame is no rallying cry

Teacher guilt is a compelling topic and it’s found its way into Emily Hanford’s reporting more than once. In Hard Words: After learning about the reading science, these teachers were full of regret. “I feel horrible guilt,” said Ibarra, who’s been a teacher for 15 years. “I thought, ‘All these years, all these students,’” said Bosak, who’s been teaching for 26 years. To help assuage that guilt, the Bethlehem school

It’s Not Enough to Know Better

Just as the school year began, Natalie Wexler’s Knowledge Gap and Emily Hanford’s At a Loss for Words shook the ground under Balanced Literacy. Optimists might assume that classroom instruction will be transformed as a result of these powerful publications, but if a teacher in my district heard the research and wanted to change her practice, she’d face a series of barriers. Barrier: Formal Evaluation The school year began with