“I wish my school were like that.”

I clicked through a slidedeck about a literacy improvement plan and I felt a pang of envy.

“I wish my work was so straightforward and my school’s progress so steady.”

But these were my slides. The students, teachers, moments captured in photographs, and ideas represented in bullet points–they were all from my school. So why, while looking at evidence of my school’s improvement, did I feel something akin to jealousy, rather than pride?

Because years of hard work, condensed into a slideshow, looked unfamiliar without the daily challenges that make school improvement so messy and progress so tenuous.

Numbers Matter, But Don’t Tell the Whole Story

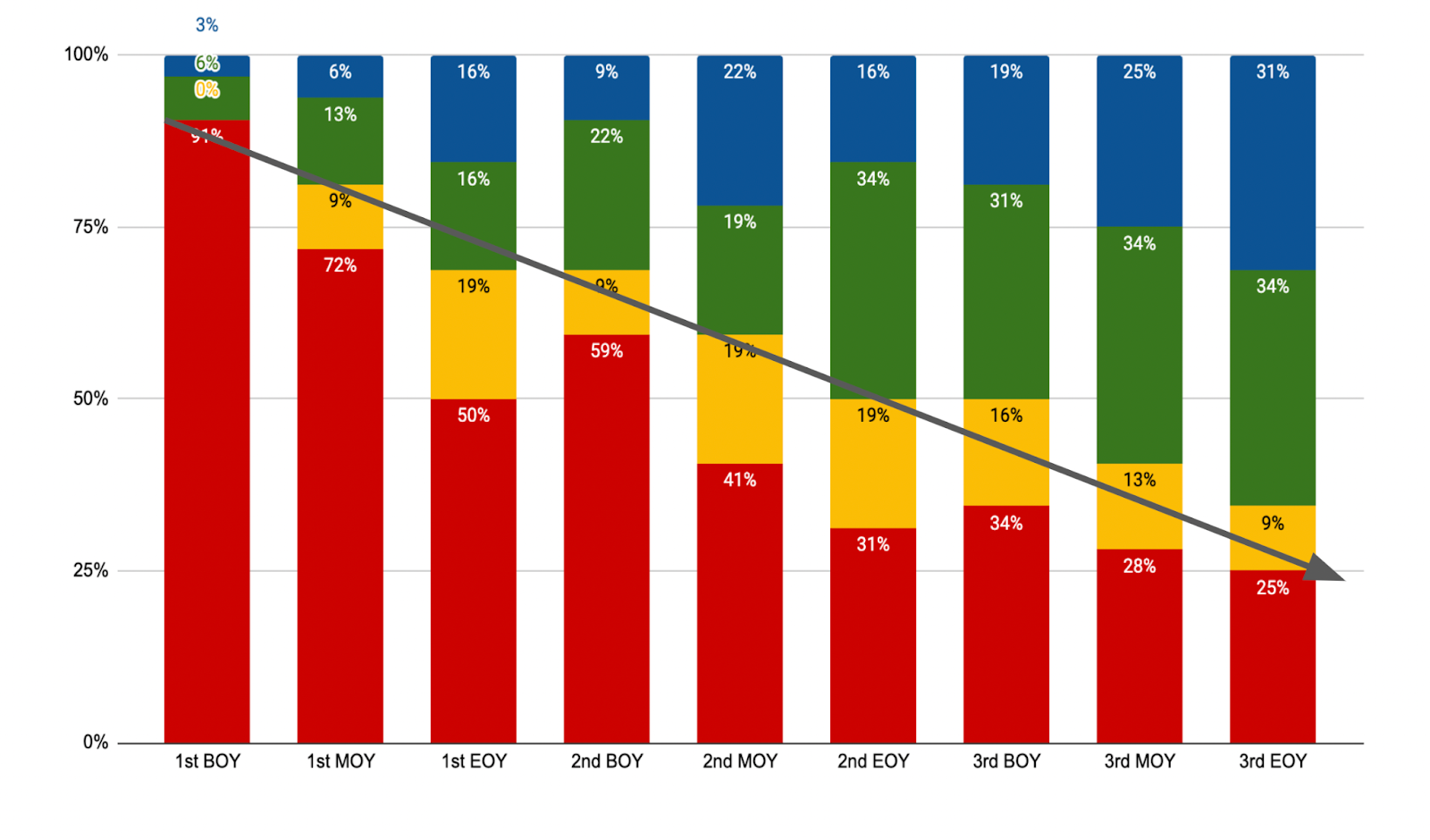

I clicked through the images and then paused on a graph of our universal screening data. A grey arrow points downwards, depicting the decrease in students at serious risk of reading failure. Over the past three years, we’ve shrunk ninety-one percent down to twenty-five.

Even though I know the numbers represent real children–kids who are on a different trajectory because they learned to read at our school–the graph doesn’t reflect how it’s felt to do this work. The reality is so much more complicated than that slide suggests. But when my principal and I display it, at an upcoming conference, we won’t have the time to talk about how bumpy things have felt.

We’ll present our plans and their impact. We’ll stick to the topics within our locus of control and examine the evidence that shows we’re making a difference. We’ll explain that the graph captures only the students who have been in the cohort all three years and we won’t focus on the fact that many students have come and gone. (Our school is next to a transitional housing shelter and so the rate of transience is high.) We’ll celebrate the number of students who no longer need intensive intervention, but we won’t talk about the gap between not being at risk of reading failure and grade-level proficiency.

On the graph, our progress looks steady, confident, and inevitable, but that’s not how school improvement feels.

Despite the Difficulties

We have plans, but executing them is more complicated than I’m ever prepared for. We improvise, make the best of things, work with what we’ve got… we do everything we can to try and make a few things better while working within an educational system that is fundamentally broken.

I don’t want to present our school as if it’s a tidy success story because I spend a good portion of the time not feeling very successful. I fret about the kids who are slipping through the cracks and the teachers who need and deserve more help than I can give. I feel exhausted when looking at how far we have to go to reach our goals and I’m terrified that not only will this work never be done, even maintaining our gains will be a challenge. Every spring, when we scrounge together short-term grants to pay for necessities, we see how easily what we’ve built can crumble.

My school is doing well despite the challenges that seem near-universal in high-poverty urban schools; chronic absenteeism, classroom vacancies, budget cuts, insufficient planning and training time for teachers.

We have a strong staff committed to ensuring the success of our students, so our problems are less crippling than neighboring schools. But it’s hard. We focus on literacy instruction despite the incessant distractions and many reasons to give up.

We Persist

I’m proud of what we’ve done at my school, but I feel conflicted about whether and how we should share our progress. I’m confident that I’m fulfilling my life’s purpose, but there are so many days in which I am bone-achingly tired, I can’t possibly sell other people on this work.

Years ago, I wanted my school to be a proof-point for the power of evidence-based reading instruction. I thought that my coaching there could be a short-term job. That seems laughable now. I still believe we need bright spots in the field, proof that school improvement is possible. We need opportunities for committed educators to learn from each other. But now I have a different, possibly conflicting hope.

I want to shine a light on the barriers that make this work so unbelievably hard. I want policy-makers, researchers, philanthropists, advocates, and changemakers to see our struggles, to study the challenges we’re facing, and to work with us to find solutions. This work is too hard to do alone.

To Get Reading Right

I worry that if people think that my school (or any school) can raise student achievement despite the current dysfunction of our educational system, they will be less inclined to fix the problems that stymie progress and threaten our collapse.

Improving literacy rates on a large scale will require solving the problems that make working in schools like mine so challenging. We can’t get instruction right within our classrooms without addressing some of the problems outside of them.

I attended your presentation at The Reading League Annual conference and thoroughly enjoyed learning from you and your principal. I appreciated that you shared how it worked for you, but also recognized that each building has a context that is specific to them and will require adaptations. I, like you, also feel such a great sense of urgency for things to change, but feel the greater systems (policy makers, funding sources) create barriers that are increasingly difficult to overcome. Thank you for sharing the success of your students. It gives me hope that change is possible, but also that we keep advocating for wide-spread change.

Three thoughts:

1) Congratulations! This is a remarkable achievement and you should be extremely proud of yourself and your team.

2) As a former third grade teacher preparing students for the reading and writing demands of the CAASP, and as a current reading specialist doing intervention for first and second graders, this is what I worry about: “We’ll celebrate the number of students who no longer need intensive intervention, but we won’t talk about the gap between not being at risk of reading failure and grade-level proficiency.”

3) When I was a high school English teacher, we participated in lots of PD related to our move from teaching anthologies to core works of literature. A colleague remarked that she always felt dejected coming out of those sessions, which she called “Being Mary” (our PD provider). Her point was that she would never have the many skills and attributes that made Mary successful despite a broken system, so this teacher yearned for an educational structure that didn’t require heroics. We absolutely need to fix the system because most of us will never come close to accomplishing what you have accomplished without structural support.

First of all, thank you so much for all the work you do at your school and for the continued contributions you make to the literacy community as a whole. You’re truly one of my heroes and when I was first learning about Structured Literacy, one of your videos about how you realized, as a classroom teacher, that balanced literacy and RW weren’t working ….well I finally felt like someone “got it”. It was my “the Emperor has no clothes “ moment. Now, years into being pretty much obsessed with teaching myself all about SOR and trying my hardest to get my “high achieving “ (if your upper middle class) TCWRP district to change, I so appreciate this post. It IS so hard and so messy to make change. And you’re right, it’s never going to get easier. Policies, funding and really our whole society addressing poverty is what has to happen. I’ve been a K/1 teacher for 29+ years. I honestly don’t have a lot of hope about all this. “The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.”

Sorry for being so pessimistic and I do truly admire your commitment to this cause. EVERY child deserves to be literate. It’s the foundation for our society and democracy.