I came into the teaching profession aware that my White middle class experience would impact how I taught. I earned my teaching credential and masters degree from a program focused on social justice. There, I’d read and discussed books such as Teaching Other People’s Children and Bad Boys: Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity, so I understood, in theory, the blindness and biases I would need to overcome.

In a children’s literature class, we’d gone to publishing houses owned by people of color and I’d learned the importance of stocking my classroom shelves with books that affirmed and expanded upon my students’ experiences. In another class, we analyzed the hidden narrative of colonialism in Where the Wild Things Are and the stereotypes in Too Many Tamales, so I knew that to negate harmful messages I’d needed a critical lens.

Because of my training, I entered the classroom armed with good intentions but without much in the way of practical teaching skills.

I did what most teachers do– I attempted to learn on the job. My first school was a high-performing, low income school, with racial diversity that made every class photo look like a carefully planned casting call. By most definitions, it was a good school with good test scores and I quickly earned a reputation as a good teacher. But even in this seemingly safe and supportive environment, the racist thinking I had been warned about crept in.

It’s not that I didn’t keep reading about culturally responsive pedagogy. And it’s not that I didn’t try to refine my practice. In fact, after reading about White microaggressions and how bias influences the discipline of Black boys, I set up a video recorder in my classroom and invited the parents of my Black boys to help me analyze the footage I collected. But my self-reflection did not result in equitable outcomes for my students. In fact, I now wonder if diving so deep to hunt for racism distracted me from the problems resting on the surface.

Normalizing Inequity

A few years into teaching fourth grade, without ever being aware of it, I came to accept the achievement gap as a simple fact of school data. The students in my fourth grade classroom who needed reading intervention were reliably children of color who were poor. Every year, they went down the hall for some extra reading help and I did all I knew how to do in the classroom. I read to my students, matched them with books they loved, facilitated rich class discussions, and I had them write, rewrite, and write some more. All the practice did result in gains, but children who came to my class behind in reading left my class only slightly less behind, I never closed the gap.

I didn’t understand that my students were struggling not because of problems within themselves, but because of the instruction they had (or hadn’t) received. I didn’t know about the assessments that would have identified the root causes of their reading difficulties, and I didn’t have access to research-aligned interventions. The daily experience of seeing students of color struggling while their White and Asian classmates excelled should have set off alarm bells, but it didn’t. Instead, my mind rang with cognitive dissonance- I accepted academic performance that broke along racial lines while believing that I held high expectations for all students.

Explaining Away Inequity

I was not consciously aware of how classist and racist ideas permeated conversations with my colleagues. Classism was cloaked in seemingly harmless phrases like, “His parents don’t read to him,” “Education is just not that family’s priority,” and “They are from out of the [school] district.” Before long, I fell inline with school staff who accepted that the chairs in the reading intervention room and those outside the principal’s office were nearly always occupied by kids of color.

“Racism is not a fixed category. It’s not what you are, but rather what you are doing and to whom.”

Ibram X. Kendi

In an interview Ibram X. Kendi defines racism as “a collection of racist policies that lead to racial inequity that are substantiated by racist beliefs,” and he explains that when faced with evidence of inequitable outcomes, a person can respond to the disparity one of two ways:

- Supporting the data with racist ideas

- Focusing on the racist policies causing inequitable outcomes

My mind flashed to the academic achievement gap.

When confronted with concrete evidence of inequity, educators often justify the status quo. We explain why, due to issues outside of our control, we can not help students who need more help. We ignore schools that are already doing what we call the “impossible.” We minimize the importance of the data we collect, even though it confirms disparities we see and hear in our classrooms. We discuss poverty and test-bias in our “progressive” circles, but we don’t often make progress.

Fixing Inequity

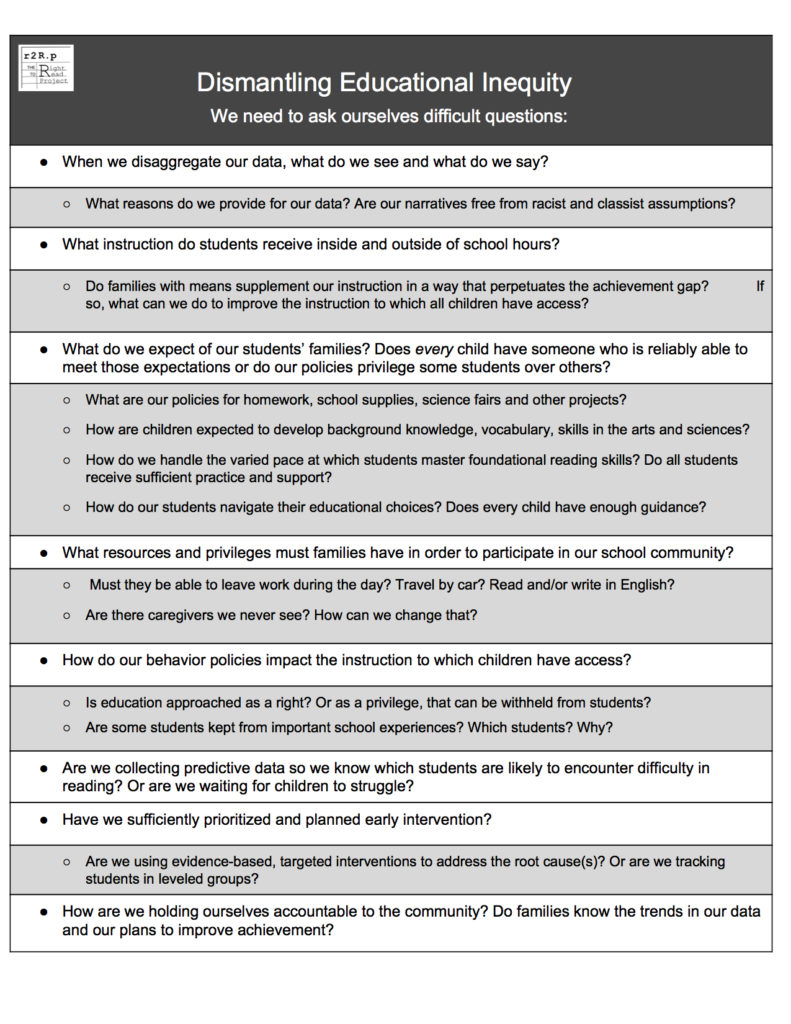

Rather than defend inequality, we need to dismantle the policies causing the achievement gap.

A recent article in the Washington Post seemed to speak directly to me:

“The right acknowledgment of black justice, humanity, freedom and happiness won’t be found in your book clubs, protest signs, chalk talks or organizational statements. It will be found in your earnest willingness to dismantle systems that stand in our way — be they at your job, in your social network, your neighborhood associations, your family or your home. It’s not just about amplifying our voices, it’s about investing in them and in our businesses, education, political representation, power, housing and art.”

I, like so many others, was spurred into deep self-reflection by current events, but I know that good intentions and antiracist theory can’t inoculate me against the racism that riddles our educational system. Facing and fixing the policies that create and perpetuate the achievement gap is the work of an antiracist educator.

“I didn’t understand that my students were struggling not because of problems within themselves, but because of the instruction they had (or hadn’t) received.”

All students struggle because of wrong instructions. Teachers teach the wrong pronunciation of sounds represented by consonants.

The rich get tuition and get better results. The poor cannot afford and end up unableto read.

Ask me any question on this matter and I will respond.

Thank you for this post. I, too spent years ignoring the gap that never closed. I blamed parents, plain and simple. Each reason that a child struggled could be tied back to the family. It never occurred to me that my instruction was flawed. I focused on solutions that make white, middle-class women like myself feel good- book drives and donations. Surely, putting books into the hands of children would solve all issues. I did not pay any attention to the fact that my students needed better instruction before they could actually read those donated books.

Thank you for your thoughtful response, Melissa. You encapsulated this flawed logic so well!

Debunked theories about how children learn to read and many weak instructional strategies continue to exist, in part, because they perpetuate the societal power hierarchy. Many of us are taught to believe that we *earned* our place in the educated elite, rather than that the system was rigged in our favor. We then try to bestow upon our students the instruction that worked for us only because we had a safety net (eg. parents who read to us, tutoring when needed, etc), but is insufficient for students who are dependent on school to learn how to read.

To realize that ALL children can be taught to read well before they leave elementary school allows us to break the cycle of privilege

Amen! As a Kindergarten teacher in 2003, I attended at District kindergarten meeting to examine new standards, identify anchor standards, and decide on common assessments. Many teachers at the meeting were adamant that this simply couldn’t be done because we couldn’t possibly expect students at our lowest achieving, highest poverty, 90% African American school to do what our students at our low poverty, primarily Caucasian school could do. My school was in the top 5 highest poverty schools in our district, was about 50/50 African American and Caucasian, and was always in the top 5, usually the top 2, for performance. We met back at our school and had a long discussion about this view. Our feeling was that just because students may come in “not ready” , or from poverty, or form a so called “at-risk” category doesn’t mean they aren’t capable or that we should lower our expectations. If we did we were inevitably setting them up to fail.

As a Reading Interventionist and now as a Literacy Coach I am still frustrated by this “poor baby syndrome”. So many early childhood and other teachers have the mindset that this poor baby can’t possibly do the work or achieve because of where he or she comes from. I’ve had so many tell me that our expectations are just too high and there is no way this child or group of children can do what we are asking. I always ask “Could your biological children meet these standards, do this work?” The answer is always, “Of course my kids can do this.” This double standard has to stop. Inequities in funding have to stop. Settling for less has to stop. The reason I love Kindergarten is that the children believe what their teacher tells them. If they are lucky enough to be with someone who believes that they are capable then they will achieve. I am fortunate to work in a school that doesn’t accept an achievement gap as inevitable but as unacceptable. Are we where we need to be? No, but I believe that we are on the right path. I welcome these discussions as a way to move us forward.

This is the time to examine our stereotypes, examine our own biases (even when or especially when it makes us uncomfortable), and start advocating for equality in education for our students. I believe it can be done. It has to be done. The time is now.