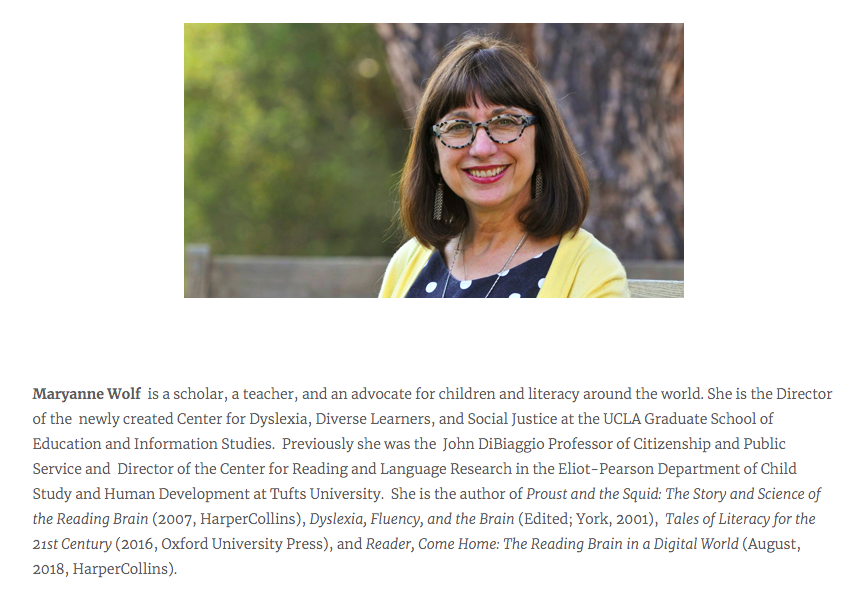

Heartfelt thanks to Dr. Maryanne Wolf for adding her thoughts this piece

More the same than different

Many of us assume that, because each child is a unique human being, every child learns to read in a different way. This widespread misconception causes unnecessary difficulty for teachers and for our students.

“It is simply not true that there are hundreds of ways to learn to read… when it comes to reading we all have roughly the same brain that imposes the same constraints and the same learning sequence.”

Dr. Stanislas Dehaene, Reading in the Brain, 2009

Understanding that each reader must master the same set of skills in order to comprehend text opens the door to a host of potential benefits:

- Better understanding of how the reading brain works

- Rethinking our teacher-training

- Determining the cause of reading difficulty

- Efficiently delivering effective instruction

- Reevaluating our beliefs about student achievement

- Teaching every child to read

| Words of Wisdom from Dr. Wolf: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Tolstoy began Anna Karenina with that famous line. In our work, each happy reader is happy because they have learned the skills necessary to become a fully comprehending reader. It may be tempting to assume each unhappy (struggling) reader is different, but each has been impeded by not having mastered some or many of the same basic skills. |

Our Training Shapes Our Beliefs

As teachers, we need to understand how skilled readers decode a text and derive meaning from it. But coursework in teacher preparation programs instead prioritizes analyzing case studies, administering surveys of students’ interests, and collecting observational data.

“The people who enter the field of education are being underserved by the authorities they have entrusted with their careers.”

Dr. Mark Seidenberg, Language at the Speed of Sight, 2017

We are taught to be attuned to each child individually and to value individualized instruction, but the research supporting our hyper-focus on differentiation is shaky at best. For example, some professional development emphasizes different “learning styles” (for more on this, see Learning Styles Don’t Exist) and long-debunked theories about how reading works (for more on this, listen to At a Loss for Words).

We are encouraged to develop our own philosophies of effective reading instruction rather than learning the science behind skilled reading. And because we are trained to value observational data over valid, predictive, reliable assessments, it’s difficult to be unbiased as we analyze the efficacy of our instruction.

Contrast our training with that of physicians: They first learn how humans are the same (e.g., basic anatomy), so as to identify well-documented and defined conditions that diverge from this. Only then do they learn how to apply this basic knowledge to the differences that can occur among individual patients.

Comparable training for teachers would include extensive study of the science that explains the teacher-training equivalent of basic anatomy – how all children learn to read.

Teachers Need to Know Every Child Learns to Read the Same Way

Every teacher should have a chance to learn what science has discovered about skilled reading as illustrated, for example, by Seidenberg-McClellan’s four-part processing model of how the brain reads.

We deserve to be taught how to use valid and reliable data to diagnose reading difficulties. And before we cultivate our own philosophies of education, we need to understand what scientists already know.

Our Beliefs Shape Our Teaching

Observing our students is a critical skill, but only when our observations are informed by an understanding of how proficient reading actually works. As cognitive scientist Dr. Mark Seidenberg explains:

“Because most of what goes on in reading is subconscious: we are aware of the result of having read something– that we understood it, that we found it funny, that it conveyed a fact, idea, or feeling– not the mental and neural operations that produced that outcome.

That is why there is a science of reading: to understand this complex skill at levels that intuition cannot easily penetrate.”

Dr. Mark Seidenberg, Language at the Speed of Sight, 2017

Most teachers are trained to observe each child’s reading behaviors, determine an instructional plan based on those observations, and deliver one-on-one coaching, which we then must monitor to begin the cycle all over again. But observations that are not informed by an understanding of the science of reading cannot guide us to the instruction that most effectively rewires the brain for skilled reading.

Without an understanding of the reading brain, these observations of reading behavior are not a good use of the precious few minutes we have to work with each student

“Parents and educators must have a better understanding of what reading changes in a child’s brain. Children’s visual and language areas constitute an extraordinary machine that education recycles into an expert reading device.

[There is no question that] increased knowledge of these circuits will greatly simplify the teacher’s task.”

Dr. Stanislas Dehaene, Reading in the Brain, 2009

When educators understand how the brain learns to read – that reading requires the repurposing of parts of the brain evolved to perform other cognitive functions – we are compelled to rethink our instruction and our assessments, and to reexamine our previous beliefs about why students struggle.

Our Beliefs Shape Our Expectations

Recently, a brave group of teachers who had shifted to scientifically-aligned reading instruction reflected on their old beliefs.

A kindergarten teacher explained to the group:

“I think teachers like to believe that every child learns to read differently because it explains our lack of success.”

The others nodded in agreement.

A second grade teacher added:

“It seems to explain the spread of abilities in our classrooms. Like, ‘They all learn to read differently and that’s why a third of my students can’t read.’ It seems to give a reason for why we didn’t reach them all.”

And another added:

“It justifies the lag. When some kids start to fall behind, we can tell ourselves, ‘Some of them are just learning differently. They’ll catch up later.’”

The belief that because each of our students is a unique individual, each one follows a unique path in learning to read, is so entrenched in our educational culture that teachers (and even parents) are not adequately alarmed when students leave kindergarten or first grade without basic reading skills.

The hardest part of coming to understand the science of reading is realizing that the learning delays we’ve come to expect in the primary grades can be an early sign of reading failure.

“We can not read the tea leaves of the behavior of five year olds and definitively determine who is going to be dyslexic and who isn’t, moreover, it’s going to depend on how they are taught.

So, we’ll cast a wide net, we’ll find the kids who seem to be falling behind, on things like “Do you know your letter names?” “Can you associate a sound with the letter?” “Have you begun to start sounding out simple words?”

There are a number of very simple sorts of measures you can use to find the children who are at risk… they get extra help, extra monitoring, and many of them will go on to become fine readers.”

Dr. Mark Seidenberg in the podcast Lexicon Valley: Why We Stopped Teaching Children How to Read

The best part of learning the science of reading is the discovery that we can raise our expectations for student and school achievement, and, consequently, improve the public perception of teachers.

Low reading achievement, more than any other factor, is the root cause of chronically low-performing schools, which harm students and contribute to loss of public confidence in our school system.

When many children don’t learn to read, the public schools cannot and will not be regarded as successful– and efforts to dismantle them will proceed.

American Federation of Teachers

So succinct yet powerful! Thank you very much for continuing to help bridge the research to practice gap.

I’m also glad to get the link to the assessments review! Do you happen to know of any freely available normed nonsense word tests?

Yes!!!

https://dibels.uoregon.edu/assessment/index/materialdownload/?agree=true#dibelseight

Super helpful for collecting information on how students approach unfamiliar words and the phonics that they know.

Learning how a child’s brain learns is essential to successful teaching. I not only train my teachers how to teach our students, most of whom are dyslexic, I also train them on how the brain of a dyslexic student learns.

Thanks so much for your article. We are recently beginning our journey of explicit instruction for reading, incorporating phonological awareness, phonics instruction, shared reading with lots of opportunities to discuss what we are reading. We are branching into how to link this to explicitly teaching writing as well. Do you have any information about approaching writing (as an intrinsically linked part of reading) with a science of reading lens?

Writing, just like reading, needs to be explicitly taught. And just like in reading, too often, students are given lots of opportunities to write, but without the instruction to accelerate their growth. There are some great options for explicit instruction in writing that you can explore, for example Writing Revolution, which teachers sentence, paragraph and essay construction. The big takeaway from the science of reading and writing is that the written code we use to represent our speech is best taught systematically and explicitly; when we expect kids to intuit it, we perpetuate inequities.