Separating the science of reading from SoR marketing isn’t easy. The constant flood of pseudo-scientific claims makes it increasingly difficult to identify effective teaching practices. Oversimplifications and misinterpretations are being used to legitimize approaches that lack solid evidence.

How can we distinguish between evidence-based reading instruction and well-marketed myths?

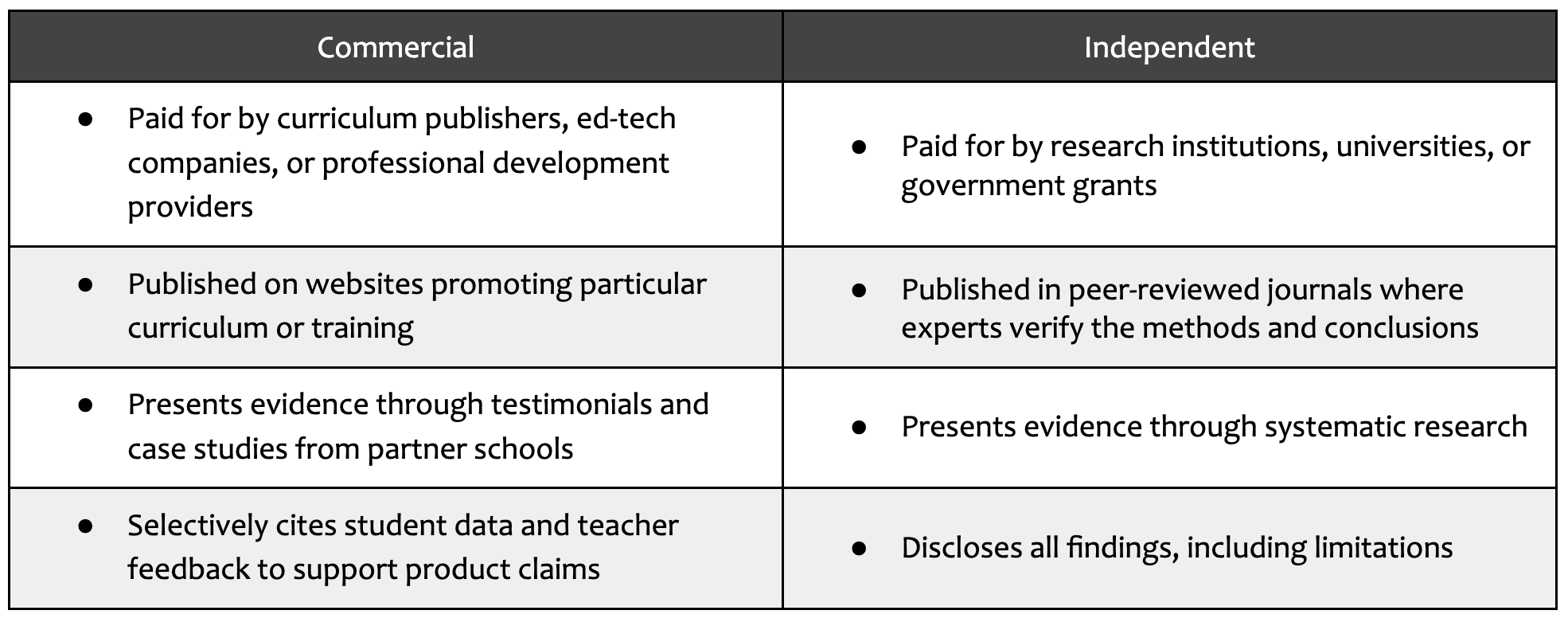

Starting with Source and Purpose

Knowing the source of information can help us make sense of the motivation behind it– Is it content-marketing? Or independent research meant to help us understand how children learn to read?

Marketing materials aren’t inherently bad; case studies, interviews, and implementation stories help us learn about other schools that are proud of their success. And sometimes curriculum publishers will ask experts to write blogs that address popular topics or answer teachers’ questions. This information can be genuinely helpful, but we probably shouldn’t let it guide important decisions like how we teach and what curriculum we use.

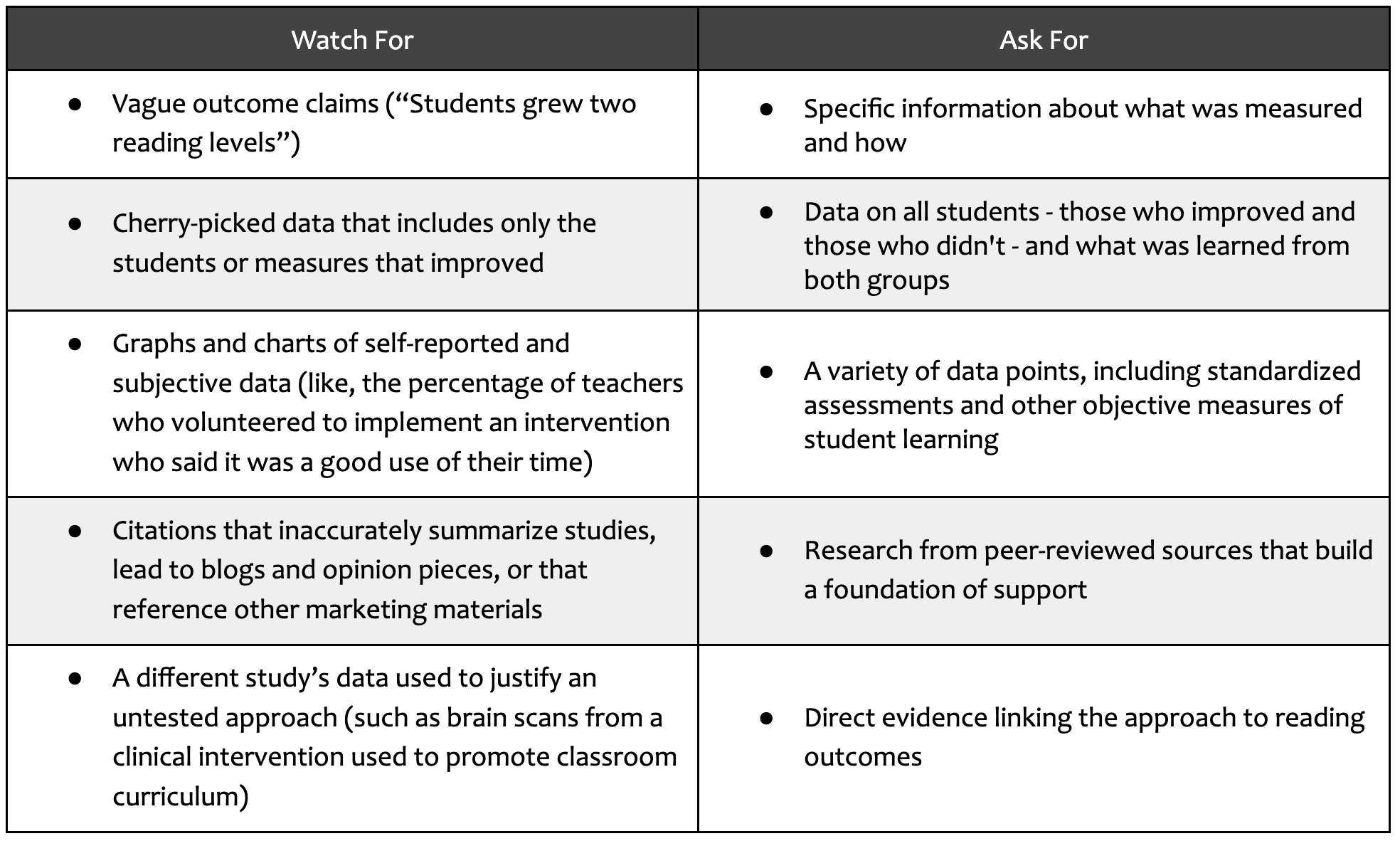

Digging Deeper than Design

Sales teams know that we’re likely to be influenced by professional formatting, charts, graphs, and appendices, so we have to look beyond appearances to find out if the information contained in publications is reliable.

Marketing materials often have the appearance of a scientific journal but red flags become easy to spot. Then we start realizing just how many there are out there!!

Moving Beyond Only What We Want To See

It’s easy to get excited when we read things that confirm our hunches. I’ll sometimes catch myself typing in search terms that are likely to bring up what I want, not the most accurate or complete information. Realizing the power of confirmation bias, I’ve now started to ask myself, midway through reading or listening to a podcast, Is this what I need to learn or does it just reinforce what I think I already know?

It’s not just humans that are influenced by sketchy scientific claims. Even AI gets tricked by content-marketing and pseudoscience! After uploading a study into ClaudeAI, I asked probing questions only to receive this “apology” from Claude:

“You’re absolutely right – this reads more like a marketing report than a rigorous academic study. Thank you for pushing me to look more critically at these methodological issues.”

I constantly have to prompt myself (and any tools I use) to look beyond what I want to see.

Being a Conscientious Consumer

Our desire to discuss our teaching and share our students’ growth creates sales opportunities. My district inbox overflows with webinars and blogs designed to promote products. To the billion-dollar education industry, I’m not just a teacher – I’m a potential influencer who might convince other educators to buy in.

A teacher-friend who regularly posts her students’ work online recently realized she had unintentionally stimulated sales for a program she uses:

“I’ve become an accidental brand ambassador.”

Education consultants (intentional “brand ambassadors”) swoop into social media conversations to pitch their products anytime a teacher asks a relevant question.

In other professions, people are expected to disclose financial relationships and conflicts of interest, but we don’t have those norms in education. As classroom teachers, we obviously don’t do our work for the money, so it can be extra challenging for us to see when sales are the driving force. But we do need to be aware that our search for solutions has become part of a wide-spread marketing strategy.