Minding the Research to Practice Gap

Following the reading research is more challenging than it sounds. There are thousands of studies and it’s hard to know where to start. For classroom teachers, making sense of studies is extra challenging because a lot (but not all!) of the research has been done in contexts that we can’t replicate– intensive doses of reading intervention, delivered one-on-one, in environments with fewer competing priorities.

So how do we make sense of a study to decide whether it’s worth our effort? The first step is understanding the language researchers use to describe their work.

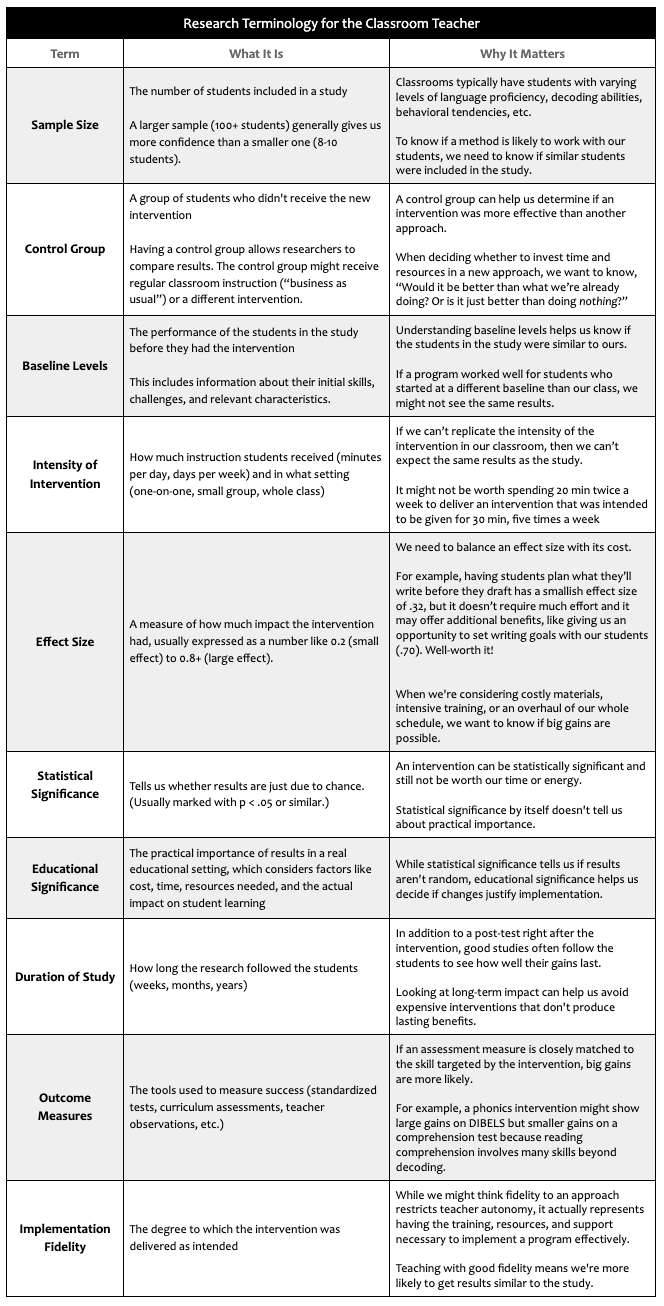

Making Sense of Research Terms

The language and structure of research papers tends to be pretty consistent. Knowing some basic terms actually goes a long way. (pdf version of this chart)

Understanding the terms scientists use can help us make sense of important distinctions in research. I once asked Reid Lyon (an early champion for the science of reading and the former Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch at NICHD) to explain the difference between two terms I had thought were synonymous, efficacy and effectiveness. He explained:

“An efficacy study is typically run in a highly-controlled environment in order to determine if an intervention has merit. But schools are complex systems… to determine if an intervention will work in classrooms, you need effectiveness trials, and effect sizes are typically smaller in trials. We found efficacy was sometimes reduced to 40% due to normal school challenges, like maintaining program fidelity and achieving sufficient dosage.”

I took a minute to think aloud about what he’d explained:

“So when teachers read studies and we feel like they are promising us results, that’s not actually a reasonable expectation because the studies aren’t often set in conditions like our own…”

He added:

“You have to make an educated guess– based on knowledge of your school, your youngsters, and the resources you have– Is this instructional method worth trying?”

Finding Relevant Education Research

Though I see interesting articles posted on social media, I usually try to select my reading from a peer-reviewed journal or curated set of resources, like those that are on this list.

When I need to quickly determine if a study is worth a close read, I’ll start with the abstract.

For an article like this, I’ll note:

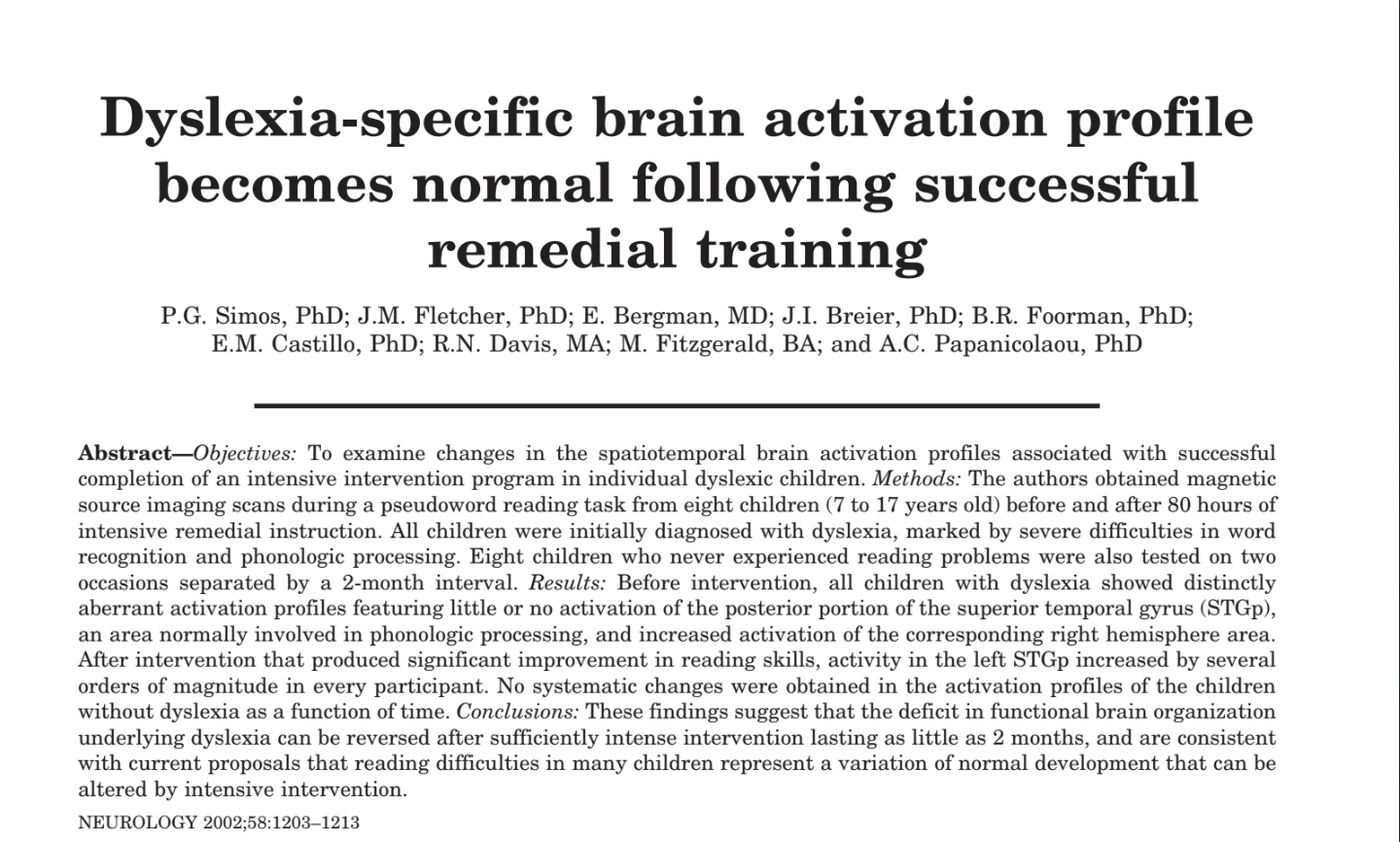

Title: makes me curious and reminds me of Jan Hasbrouck’s quote, “Instruction is brain surgery!”

Authors: reliable researchers (Fletcher, Foorman, etc.)

Sample size:

- small, 16 students

- 8 students, of varied ages, all with severe decoding difficulties

- 8 students who never had reading problems

Intensity of the intervention: 80 hours of intensive remedial intervention in two months

And at this point, I’ll stop and think about the relevance of the study to my classroom instruction. I would need to find two hours a day to work one-on-one with students in order to put this intervention in place. This study shows something important– intensive intervention seems to help rewire the brains of struggling readers, regardless of their age– but it’s not feasible to attempt this instruction in my classroom. I might read and discuss this study with a friend who does tutoring, but it doesn’t offer super relevant guidance for my classroom instruction.

A related note:

If I find an abstract of interest but it’s behind a paywall, there’s usually an email address for the author(s). A short, friendly email does the trick and I use my school address so that they know that I’m a teacher. The author will typically send me a pdf version within a couple of days. Then I can skim the article (or upload it with some targeted questions about the intervention and findings to ClaudeAI) to determine how much time and attention I should devote to reading it.

Valuing Meta-Analyses

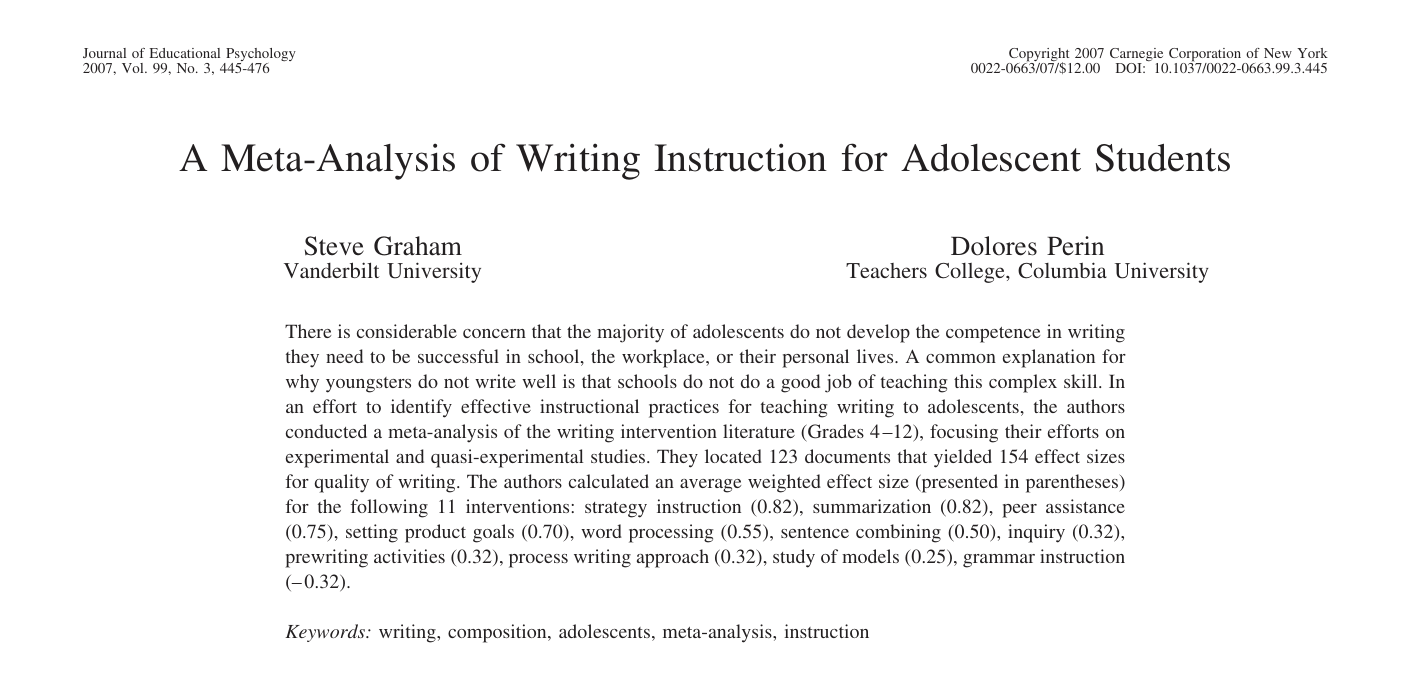

Meta-analyses help me find evidence-based teaching strategies because they review the literature on a particular topic and summarize the findings. For example, the paper below served as a basis for training in SRSD Writing that several of the teachers at my school attended.

If I didn’t have the time to carefully study the whole paper, I would have zeroed in on the strategies that had the greatest effect sizes–I’d read the descriptions of each to see if my teaching seems similar (sentence combining? ) and if there are strategies that I should explore (peer assistance! setting product goals!)

Then, I’d skim down to the section labeled “Discussion” to read the specific points that the authors wanted to emphasize. The section called “Limitations” is especially important because it explains how far we can/should go, if we’re drawing our own conclusions about implications. This particular article is especially educator-friendly because it has a section titled “Issues Involved in Implementing the Recommendations.”

I typically hunt for articles that evaluate instructional strategies possible in the classroom environment with students like mine. There’s quite a lot of articles that fit those criteria, but even more that don’t, and so I save myself a lot of time!

Braving the Research-Practice Divide

Though I’d love to get a PhD in statistics or methodology, I’ve found I can still sift through publications to find ones that are useful. Articles often connect me with researchers. Sometimes, I’ll ask follow up questions to make sure I’m on the right track with my interpretation:

- So, am I right in inferring that…?

- Is it safe to say that…?

- How would you want a teacher, like me, to apply what you’ve learned?

Asking our teacher-y questions can be intimidating, but I remind myself that it’s my job to balance the evidence with my professional judgment about what’s feasible and worthwhile in my classroom. The more discerning teachers become about research, the more focused and effective we can be in raising our students’ achievement. We couldn’t possibly work any harder. Working smarter is the only option.

Very valuable information. Thankyou for sharing it.