Planning with the creative and hard-working teachers on my fourth-grade team was rewarding (and occasionally hilarious), but our enthusiasm sometimes produced overly-complicated plans. If a plan was becoming unwieldy, one of us would interrupt the process and say to the team:

“If it’s this complicated, it’s probably not right.”

We’d then pause, rearticulate our goals, and start over to create a more coherent instructional plan.

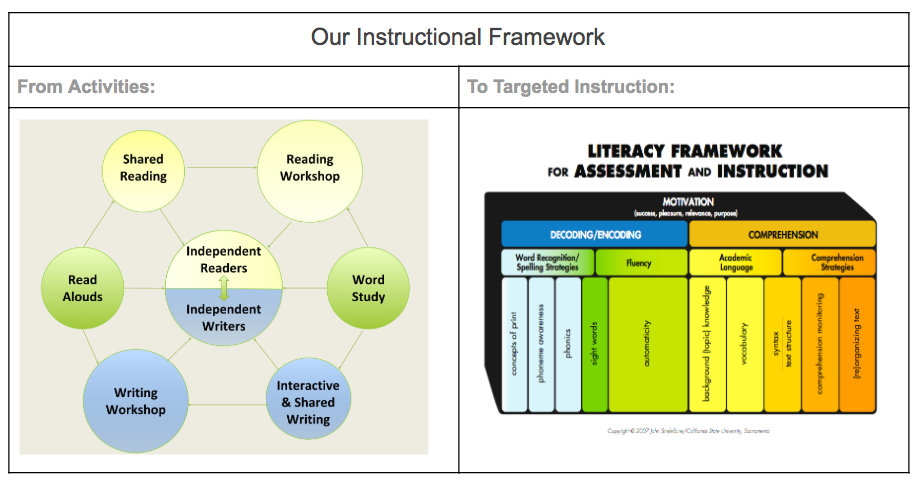

Thought leaders in the Balanced Literacy community are engaged in a similar process of reexamining plans for instruction. But as they review research and respond to the national discourse about reading, teachers are receiving increasingly complicated messages about reading instruction.

It Seemed Clear at First

Balanced Literacy used to provide us a clear plan:

- Teach phonics and allow plenty of time for authentic reading and writing.

- Use predictable texts for beginning and struggling readers.

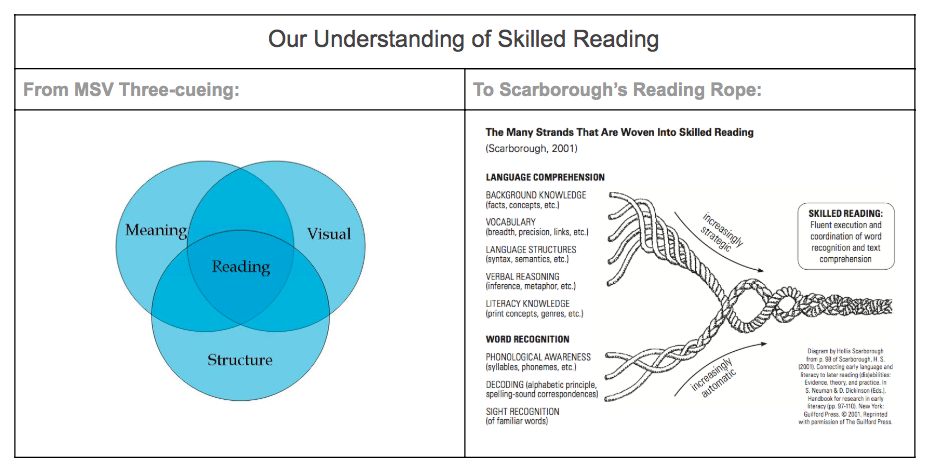

- Assess students using MSV analysis on reading records.

- Explain reading as an orchestration of meaning, structure, and visual cues.

But Then It Got Complicated

A flurry of recent articles (eg. Getting Reading Right) questioned this plan for instruction, so leaders in the Balanced Literacy community added new layers to their earlier messages. Those of us in Balanced Literacy districts now wonder:

“What does this mean for our reading instruction?”

It may be time for us to pause, rearticulate our goals, and revise our plan for teaching reading.

Our Goals

We want every child to learn how to read authentic texts fluently and with deep understanding.

Nonstarters:

- Phonics-only instruction

- Surrounding kids with books and hoping for the best

- Maintaining the status quo

To ensure every student becomes a strong reader, we’ll need to make some instructional changes and we might want to start by unraveling some of Balanced Literacy’s recent complications.

Complication #1: Don’t Focus on Phonics, But Learn More About It

Leaders of Balanced Literacy have critiqued the national discussion about reading for being “phonics-centric,” but they also acknowledge that teachers need to learn more about phonics.

“We find that not all teachers have strong understanding [sic] of the alphabetic system and it’s very difficult to teach children how to use letter sound relationships, how to use word parts if they don’t understand themselves the logic in the alphabetic system.”

“Teachers— especially those teaching pre-K to second grade—do need to learn more about phonics. Even teachers who have taught a phonics program for years sometimes haven’t learned all they need to know.”

District leaders and those who train teachers are left to wonder, “Should we provide professional development about the alphabetic system? Or should we stop talking about phonics?”

Complication #2: Yes, MSV but no “three cueing”

Proponents of Balanced Literacy have downplayed the role of three-cueing in reading instruction since Emily Hanford’s At a Loss for Words.

Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell popularized the practice of coding student reading errors with MSV (meaning, structure, visual), but they have recently distanced themselves from the practice:

“There’s a lot of misunderstanding around what some people are calling three cueing systems, and I think it’s related to maybe some coding that teachers are using.”

Gay Su Pinnell

In that same interview, Fountas described three-cueing analysis:

“[Teachers] can actually see what aspect of visual information or letter, sound relationships children are actually using in the reading process, with the meaning and the language [structure] of the text…”

But she closed this sentence by saying:

“…and we do not mean three cueing systems.”

Pinnell explained:

“[Students are] using different sources of information, but it’s not necessarily three.”

Their comments left many of us wondering if we should stop analyzing for MSV. Without three-cueing, it’s difficult to explain the purpose of miscue analysis.

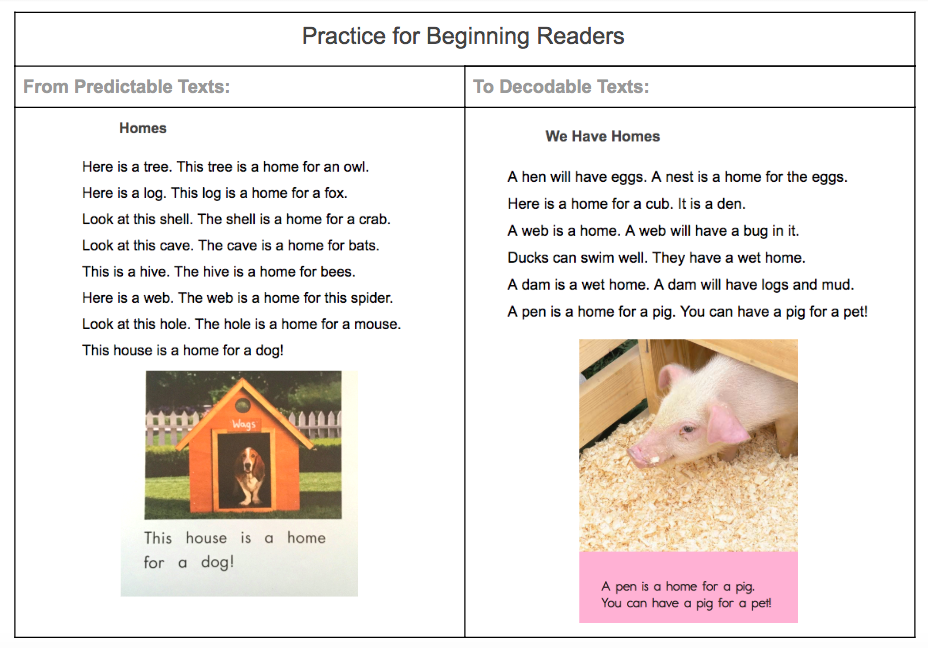

Complication #3: Try a mixture of predictable and decodable texts

Simply put:

Decodable texts teach students they should decode words.

Predictable texts teach students they should predict them.

To determine whether to scaffold beginning readers with decodable or predictable books, we need to consider how we want students to approach words once they are ready for authentic texts. Do we want students to sound out unfamiliar words? Or hunt for clues and then cross-check with the letters?

Simultaneous instruction in both decoding and predicting words is not only confusing to students, practice in one will undermine student progress in the other.

Texts that are designed to teach students to use strategies other than decoding- cueing based off pictures, syntax, and first letters- discourage children from sounding out words.

“The last thing children who are dyslexic need is encouragement to compensate by relying on pictures and meaning instead of sound-letter correspondences. They need books that help them rely upon the letters on the page and to trust that the phonics instruction they receive will pay off when they are reading continuous texts.”

Fountas:

“The real measure of effective phonics instruction is how children use that knowledge as readers and writers… Kids need to know why they’re learning what they’re learning about letters, sounds and words and how they’re using it as readers and how they’re using it as writers.”

Calkins:

“Decodable texts have value for all children in the earliest stages of learning to read.”

Calkins explained that predictable texts are for “approximating reading.” In the pre-reading stage, simulating reading has value, but it does not make sense once reading instruction has begun. Students need books that allow them to apply what they are learning about the alphabetic code.

If we no longer believe that skilled readers use meaning, structure, and visual cues to predict and cross-check words while reading, we have little need for predictable texts for instruction in the primary grades.

If all beginning readers benefit from decodable texts and some students are harmed by predictable texts, should primary grade teachers remove predictable texts from their classrooms?

Finding Clarity

As Balanced Literacy leaders distance themselves from MSV instruction and the student texts and assessments that go with it, teachers are left holding instructional materials without a rationale for implementing them. Without the three-cueing theory of reading to rely on, the Balanced Literacy community lacks a clear explanation of how we read, the books students should read, and how teachers should assess.

Educators face a choice:

We can wait and see how the leaders of Balanced Literacy revise their materials.

-or-

We can start making changes to benefit our students this school year.

For those of us who are willing to embrace change now and revise our plan for teaching reading, below are some shifts we might consider.

The conversation about Balanced Literacy has become overly complicated. Let’s pause.

“If it’s this complicated, it’s probably not right.”

We can clarify things for ourselves and on behalf of our students by grounding ourselves in reading research.

As Calkins wrote:

“I am grateful to the science of reading proponents. I also am grateful that these educators are successfully calling attention to the importance of prioritizing professional education for teachers. I think that professional education is necessary for those of us in teacher education as well. I, for one, have benefitted from this discussion and am grateful to be on a learning trajectory.

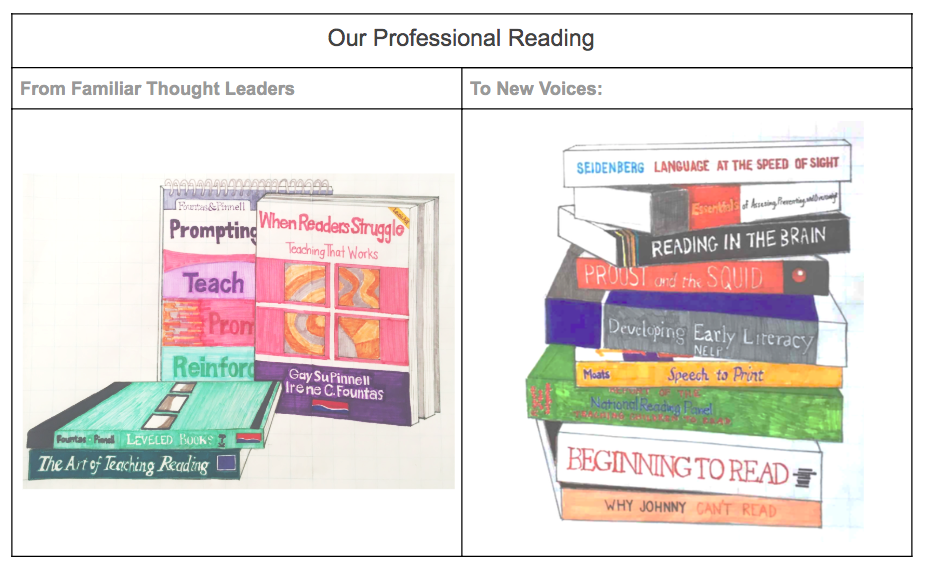

The leaders we’ve looked to in the past are on a learning journey. Instead of waiting for them to get back to us with their discoveries, let’s join in, learn together, and build a new plan for teaching reading.

Why Johnny Can’t Read isn’t a new voice and I have long wondered if its attack mode isn’t what drove the whole language folks into their defensive camps.

You make an interesting point!

Several of the books in the stack are not “new” (eg. Beginning to Read from the 1990s), but given the way Balanced Literacy evolved, maybe they weren’t properly heard.

Not properly head….I love that idea. I wish someone could tell me why Jean Chall did not read the original reading war and why the Goodmans/Marie Clay/etc did.

Excellent

Well done right2readProject. You continue to build clarity and build bridges that support teaching colleagues, instructional conversations, and better outcomes for kids.

This is so positive and inspiring. It would be great if your references could be cited too. It all helps deepen the research.

Excellent job breaking down the information and laying out a clearly defined path so that every child can access his or her right to read.

Thank you for your voice. We can all (including the gurus) learn from this succinct explanation of the state of early literacy instruction, Dec 2019. Meanwhile, there are eager learners in every classroom who deserve instruction based in the established science of reading. Let’s keep this critical conversation going and adjust teaching practices as needed, to best serve all children.

What is the title of the second book listed in the suggested reading box?

If you’re counting up from the bottom: Beginning to Read, by Marilyn Adams (an oldie but goodie)

If you’re counting down: Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties, by David Kilpatrick (a book we reference ALL the time)

This piece, along with Emily Hanford’s recent podcast on Educate, New salvos in the battle over reading instruction, do a good job highlighting all the mixed messages from balanced literacy proponents.

Thank you for having this important discussion.

I love that the “new voices” in the graphic are mostly OLD voices that we have been ignoring or have been told to ignore for years. THANK YOU for bringing a sane, research-based plan to the masses.

Hello,

Would you be able to recommend a professional development workshop or program on how to best teach decoding to 1st/2nd graders? Secondly, I am would also love to attend a thorough workshop or program how to best develop 1st-3rd graders “language comprehension,” i.e., curriculum that builds knowledge and vocabulary, and provides assessment guidelines to see if what are doing is having the desired reading results with our students.

I am growing in my understanding of what doesn’t work, but am unclear on how to gain the skills to teach what would be best for our students.

Thank you!

Great question! There is wonderful PD available through a variety of different organizations, many of which are regional. There are a few nation-wide options for reading science PD, like LETRS (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling) and CORE Reading Academy (which uses the CORE Teaching Reading Sourcebook). There are also organizations like The Reading League, 95% Group, and LiteracyHow that provide in-person PD on a variety of topics. And some great online resources (Reading League YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCm9TD9u7xGdRUaGjHkOthxw) and Reading Rockets (https://www.readingrockets.org/teaching/reading101-course/welcome-reading-101)

You may also want to contact Richard McManus (rgmcmanus@fluencyfactory.com), who runs The Fluency Factory (www.fluencyfactory.com) in Cohasset, MA. He’s a phonics expert who has years of experience working with early-elementary students, and he’s looking to move more into training teachers.

When error analysis is done thoroughly by a teacher that understands the intricacies of the code and morphology, specific insights can be gained about that child’s decoding gaps and the subsequent explicit instruction needed. There is a lot more to it then choosing a “v”, and choosing that “v” is pointless if it does not lead to targeted code and/or morphology instruction. It was a team project in error analysis (both with running records and Fundations decoding tasks) that really began to lead our team (Title 1)to the science of reading, and now we cant get enough personal PD in SOR!!!!!